In a busy hospital, noisy correctional facility, bustling campus, tragic crime scene, and orderly military aircraft, chaplains stand as an unwavering support system for spiritual needs. These ministers’ pulpits are not found in churches but extend into the everyday human experience.

Campus

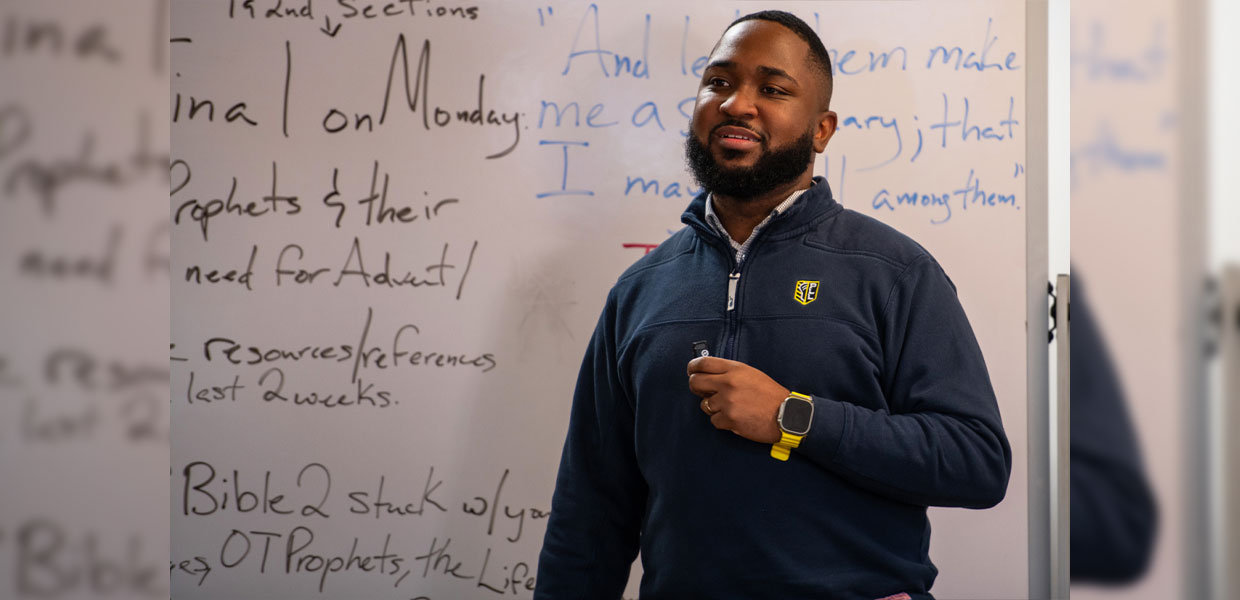

Jelani Jackson, Atlanta Adventist Academy chaplain and Bible teacher, provides spiritual support to approximately 130 high school students, with about two-thirds attending virtually.

Establishing meaningful relationships is crucial to his role, stated Jackson. “There is a lot of mistrust of people in authority [among this age group],” noted Jackson. He uses various techniques to show his students that he is relatable, and students can confide in him.

Jackson’s class is often filled with laughter, having successfully fostered good relationships with students. But, beyond addressing spiritual questions, praying for students, and teaching Bible curriculum, he also explores students’ stressors, with school being a significant concern.

Jackson acts as an advocate for students, seeking ways to reduce school-related stress in students’ lives. Additionally, he has navigated student mental health crises, assuming a counseling role to offer encouragement and helpful resources.

Despite the challenges, Jackson finds the work rewarding, emphasizing the joy of daily interaction, and privilege of walking alongside students on their spiritual journey.

“At first, I didn’t know if I wanted to be a school chaplain,” said Jackson. “… but now that I’ve done it, I really love it and it’s been a blessing.”

Community

José Antonio Pagán, MAPM, a volunteer police chaplain and Central California Conference Adventist Youth Ministries director, differs from the law enforcement agents he works alongside — he serves without a salary and without carrying a gun.

After 33 years of ministry and community involvement, he became a law enforcement chaplain, drawn by the opportunity to interact with a diverse group of people and meet the community’s needs.

In his capacity, he provides spiritual support to the police department’s employees, their families, victims, and victim’s families. Among several heartbreaking situations, one of the toughest moments occurred when his life was threatened by a victim’s family member. However, it was not the threat that saddened him, but what happened immediately afterwards. Assigned to ensure the team’s safety, an officer made the decision that it wasn’t safe for Pagán to engage with the victim’s family. This meant Pagán, despite his desire to offer comfort, had to step back and could not complete his chaplain duties.

“It’s tough when you have your hands tied and you have your heart available, but you can’t do anything else,” shared Pagán.

Pagán said he values his role as police chaplain, stating it opens doors to a community outside the Church. “It’s a big privilege, a wonderful opportunity to be close to people in a completely different aspect of ministry and religious environment,” said Pagán.

Corrections

Lester Bandy, M.Div., chaplain at Lee Correctional Institution, responds to various needs from more than 1,000 men incarcerated there. In addition to praying and leading chapel, Bandy provides encouragement, supplies spiritual materials, and connects incarcerated people with their families.

In prison, people commonly conceal challenging emotions, especially separation and grief, according to Bandy. “Grief ministry in the prison setting is not like in a hospital. There is some taboo when it comes to talking about grief,” said Bandy.

This has been challenging for Bandy as he desires to meet not only the incarcerated men’s spiritual needs, but also their emotional needs. To help facilitate conversations on emotions, including grief and depression, Bandy has spent two years developing a non-religious program that will focus on the day-to-day emotional needs of those incarcerated.

Healthcare

Makeba Garrison, D.Min., a healthcare chaplain in Memphis, Tennessee, felt a calling to shift her ministry focus after 15 years of teaching. Instead of pursuing a doctorate in education, she pursued a master’s in divinity with a focus on hospital chaplaincy.

Today, Garrison works in a children’s hospital where she interacts with patients, patients’ families, and staff daily. Her approach varies: she engages some children in games or music, and offers a quiet presence for children who are easily overstimulated. Garrison supports patients’ families by advocating for them and allowing them to grieve during difficult times.

“A healthcare chaplain shows up with the agenda — to make a family feel safe, seen, and loved in probably the worst time of a family’s life,” explained Garrison.

Garrison also provides spiritual support to the hospital staff. In addition, Garrison meets with fellows and residents monthly to affirm them in their vital work.

Juleun Johnson, D.Min., vice president of mission and ministry for the AdventHealth Southeast Region, works closely with chaplains and leadership across AdventHealth facilities in Georgia, Kentucky, and North Carolina. Johnson emphasized the essential role of chaplains in healthcare, offering spiritual and psychosocial support to staff, patients, and visitors.

“Chaplains are viewed by many persons in the hospital as essential to the healing process,” stated Johnson. “… The chaplain is an important member of the team.”

According to Johnson, many Advent-Health employees identify as non-religious. Johnson views the hospital as a mission field — an opportunity to show Christ to others. Chaplains prioritize making relationships with staff, fostering trust that encourages open dialogue.

“As a chaplain, you get the opportunity to walk with people and celebrate people, but also stand with people at the most crucial points of life,” reflected Johnson. “It’s a blessing to be able to be connected with the staff members, because they are the heart and soul of the hospital.”

Military

William Dykes, M.Div., U.S. Army chaplain, enlisted as a chaplain’s assistant at 17 to fund his Adventist education, the sole Army role related to ministry available without a college degree. While attending college, Dykes participated in weekend drills and was deployed for a time, often leading religious services for troops in units lacking chaplains.

Upon completing his M.Div., Dykes pursued his goal of becoming an official Army chaplain, a role requiring not only a master’s degree and endorsement, but also two years of full-time ministry experience. To gain this experience, he worked as a chaplain at Florida Hospital for Children, now AdventHealth for Children, where he developed his personal philosophy of ministry.

Transitioning to the Army chaplaincy, Dykes describes himself as a “muddy boots chaplain,” because of his active engagement in training and diverse activities rather than being confined to an office.

“I want to be where [the soldiers] are because I saw Jesus as the God who pursued. So wherever they are, I want to be out there in the field, or, if they’re going to the range or jumping out of planes, I want to do it too,” said Dykes.

His duties are multifaceted: from conducting religious services on both Sabbath and Sunday to advising battalion commanders on ethical matters, providing counseling, organizing family events, and even offering assistance with personal matters like taxes and childcare. Dykes puts it simply: “Whatever it takes, I want to be there for them.”

Critical Ministry

Regardless of the area of ministry, chaplains within the Southern Union fulfill a vital role. In crucial times, their unique position allows them to engage with individuals who otherwise may not have sought spiritual support.

Christina Norris is the associate communication director for the Southern Union Conference.

Comments are closed.